Scientists have described nine new species of ancient insects

Two new genera and nine new species of caddisflies have been described by researchers from St Petersburg University, the Borissiak Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and Cherepovets State University. Caddisfly are winged insects that have a common ancestor with butterflies. The scientists did their research using a collection of stones with prints of arthropods, which had been gathered in the territory of Stavropol.

The insects, according to the experts, are about 13 million years old. The findings of the research are published in Paleontological Journal.

Caddisflies can be found in virtually any part of the world today from Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean to the outskirts of the Sahara Desert in Africa. These insects resemble small, dull-coloured moths. But unlike their distant relatives, caddisflies predominantly have an aquatic lifestyle - they lay eggs in lakes, rivers and streams where their larvae develop. In addition, they are well known to fishermen, because insects are often used as complementary food or bait for fishing.

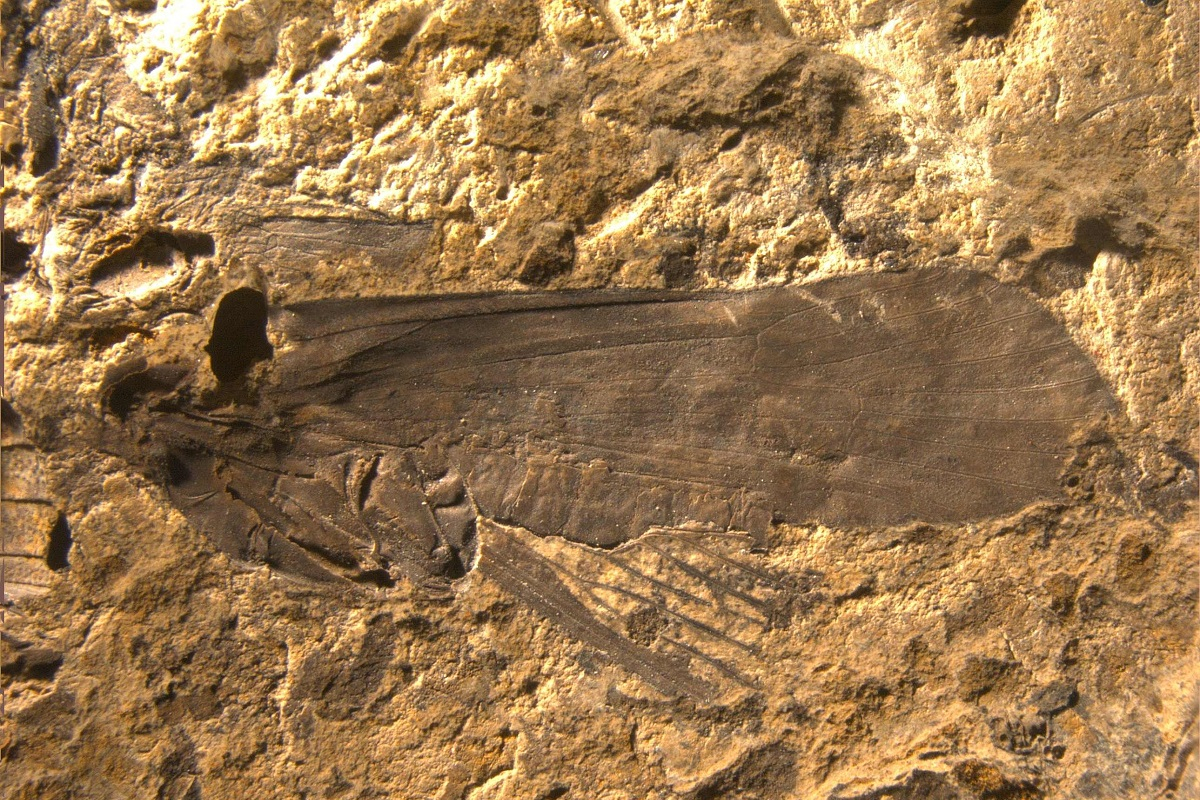

A large collection of prints of caddisflies was gathered as far back as 1939. The expedition of the Paleontological Institute went to the vicinity of Stavropol, to the locality of Vishnevaya Balka and to the village of Temnolesskaya. On the banks of two rivers, the scientists succeeded in finding many insects "sealed" in the Miocene sediments: a total of about 3,000 items. Among them were the ancient dragonflies, mayflies, water beetles, bugs and caddisflies – every fifth creature from the collection was a representative of this order. Different scientists tried to gain insight of the palaeontological data in different years. This description problem has been solved quite recently with the help of modern methods of digital image processing.

Software applications that enable you to change the contrast of the image made it possible for us to see the slipping parts that the human eye does not usually recognise. Almost like restorers find hidden images on icons, we found subtle structure features of the caddisflies on the prints and were able to interpret them.

Vladimir Ivanov, a co-author of the research paper, the Head of the Department of Entomology, St Petersburg University; Candidate of Biology

As a result, the researchers managed: to redescribe the species Limnephilus kaspievi, known since 1939; to describe two new genera - Miocenocosmoecus (as part of the family Limnephilidae) and Calamostavropolia (as part of the family Calamoceratidae); as well as to describe nine new species of caddisflies: Limnephilus parakaspievi, L. quasikaspievi, L. metakaspievi, L. valliculacerasinus, L. antiquastepposus, Potamophylax martynovorum, Halesus miocenicus, Miocenocosmoecus silvacaliginosus, Calamostavropolia revolutionaria. It is easy to guess that some insects were named after localities: for example, the species name silvacaliginosus comes from the Latin words silva (forest), caliginosus (dark) and means the village of Temnolesskaya.

The research was carried out by: Irina Sukacheva, a senior researcher of the Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences; Stanislav Melnitsky, an assistant professor, St Petersburg University; and Daniil Aristov, an employee of the Paleontological Institute who is also a lecturer at Cherepovets State University. The findings have also raised many new questions for scientists. Between one and five species of caddisflies Limnephilus can live together in the modern fauna. This number of species is not a lot compared with earlier times. Ancient findings show that nine species could have lived together in the Stavropol Region 13 million years ago. Another suggestion is that the various fossil finds of caddisflies could be representatives of the same species, but at different stages of evolution. Or their individual differences may have been changes within a single population. For example, their wings and legs were just changing, as the faces of different people change. The scientists note that to finally understand these issues it is necessary to conduct additional research.

“Interestingly, the Calamoceratidae family indicates a relatively warm climate – tropical or subtropical – but the Stavropol Region is not tropics or subtropics,” said Vladimir Ivanov. “This happens as some tropical species may spread to non-tropical areas. For example, other genera from this family live in the south of Primorye. They have adapted to spend the winter in hibernation, and in summer in that region it is warm and very damp – almost like in a tropical forest.”

Such fossils help researchers not only learn more about climate change, but also, for example, about the features of the landscape. The Stavropol caddisflies lived near an estuary. This was discovered when the scientists found ancient marine molluscs along with insects.

Moreover, the research into caddisflies helps the study of the evolution of species. In the future, it may force entomologists to revise some existing theories about the distribution of caddisflies on the planet. The findings of the work will still be useful today: ancient insects can help to determine the age of geological deposits on ancient continents, which are now difficult to date. It is important not only in academic activities, but also during exploration and production of oil and other minerals.