100-year-old casts of lizard skulls restored and their 3D models made at St Petersburg University

At St Petersburg University, they have restored and made 3D models of plaster casts of the skulls of Permian lizards. They were created more than 100 years ago under the supervision of the famous palaeontologist Vladimir Amalitskii. It is noteworthy that the casts were moulded from fossils, which Amalitskii had previously discovered a lot of in the Arkhangelsk region.

St Petersburg University prepared an exhibition to mark the 160th anniversary of the birth of Professor Vladimir Amalitskii, a Russian geologist and palaeontologist and a University graduate. It was decided to restore replicas of three lizard skulls for the exhibition. The fossils used for the casting were discovered by the famous palaeontologist in a sand lens on the cliff of the Small Northern Dvina River at the end of the 19th century.

‘Replicas of the vertebrate skulls of the Severodvinsk Gallery were made in the Palaeontological Laboratory in Warsaw under the supervision of Vladimir Amalitskii. They were created around 1908–1914, as indicated by historical records and literary sources. The replicas of the skulls are likely to have come to the Palaeontological Museum of St Petersburg University through the Geological Cabinet of the Higher Bestuzhev courses for women, as many University’s professors were involved in their organisation,’ said Vadim Glinskiy, Head of the Department of Natural Science Collections at St Petersburg University.

According to Vadim Glinskiy, Amalitskii's discoveries are directly related to the history and people of the University. From 1887, Professor Amalitskii worked as a curator in the Geological Cabinet. At present, it is known as the Palaeontological and Stratigraphic Museum of St Petersburg University. A research collection of Permian molluscsanthracosides is kept there. The collection triggered all subsequent amazing discoveries of the scientist. Casts from the fossil skulls of lizards, exhibited in the museum, complement the story of Professor Amalitskii's discoveries. They are of high historical and scientific importance – that is why it was necessary to restore them.

The restoration of skulls’ casts of the Permian lizards – Scutosaurus, Inostranсevia and Dvinosaurus – became the graduation project of Ekaterina Ageeva. She is a graduate of the Department of Restoration at St Petersburg University, a representative of a new generation of University students. The work was carried out under the scientific supervision of Vladimir Torbik, Associate Professor in the Department of Restoration, and Dina Fomitova, Assistant Professor in the same department.

As a result, the lost parts of the nasal bones of the Inostranсevia and quadratojugal bones of the ‘protective collar’ of the Scutosaurus were restored. The parts of the skulls with chipped paint were also tinted, while the original paint coat of the surface was not affected.

Scutosaurus (Scutosaurus karpinskii) were the first saurians whose entire skeletons were found and exhibited in Russia. The name (from the Greek words scutum - shield and saurus - lizard) reflects the peculiarity of animal skin. It had a large number of scutes (osteoderms), which served as armour. Scutosaurus were up to three metres long. According to one hypothesis, these slow herbivorous animals were semiaquatic – like hippos.

The natural enemy of the Scutosaurus was Inostranсevia (Inostranсevia alexandri). It was a therapsid, with the body length reaching up to three and a half metres. Inostrantsevia had huge canine teeth about 30 centimetres long, which were replaced throughout life.

Inostrancevia was named by Vladimir Amalitskii in honour of Professor Aleksandr Inostrantsev, his research supervisor, teacher in geology and founder of the Geological Cabinet at St Petersburg University.

Another predator, but much smaller, was the Dvinosaurus (Dvinosaurus primus), an amphibian that got its name from the proximity of the excavation site to the Northern Dvina River. The length of the animal was about a metre. Dvinosaurus spent all their life in water, without crawling out onto land. For breathing, Dvinosaurus used external gills, which resembled present-day axolotls - salamander larvae - ambystoma.

The restoration work was greatly complicated by the coronavirus pandemic. In February and March, I worked with documents, took photographs of casts. Already in April, the lockdown made access to the University impossible. However, despite the forced delay, we still managed to complete all the necessary work in due time.

Ekaterina Ageeva, a master’s student at St Petersburg University

‘The greatest difficulty was with the skull of Inostranсevia. To restore the lost nasal bones, we requested photographs of the original fossil skull from the Orlov Palaeontological Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences, which is located in Moscow. My supervisors were Vladimir Torbik and Dina Fomitova, as well as Vadim Glinskiy, Head of the Department of Natural Science Collections at St Petersburg University. They advised me in this work which is at the intersection of restoration and palaeontology,’ noted Ekaterina Ageeva.

Ekaterina Ageeva is currently a first-year master's student in the Restoration of Fine and Applied Art Objects programme at St Petersburg University. According to her, the University has unique casts and sculptures of ancient saurians and other extinct vertebrates, which she would like to restore in the future. Under the supervision of Vladimir Torbik, Associate Professor in the Department of Restoration at St Petersburg University, the catalogue cases of the Museum were also restored from the ruined state. Now they contain part of the research (monographic) collection of Vladimir Amalitskii.

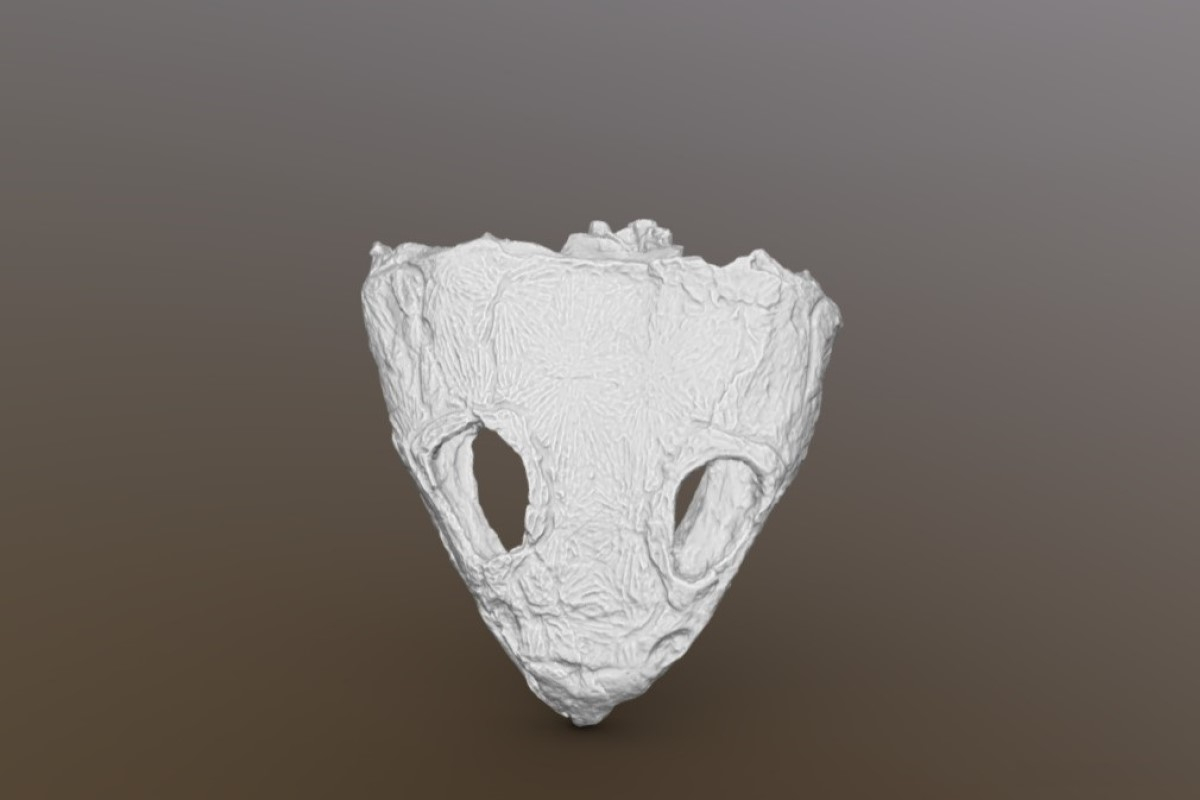

After the restoration of replica skulls of lizards, their precise 3D models were created using the high-precision 3D scanner RangeVision Spectrum. This work became possible thanks to Dmitry Grigoriev, Associate Professor in the Department of Vertebrate Zoology.

‘3D models of objects are very instrumental, as they offer a greater amount of accurate information and make it possible to avoid using costly objects for the teaching and learning process and particularly routine research work. The use of three-dimensional models of skeletons greatly simplifies the study of comparative anatomy of animals,’ says Dmitry Grigoriev.

Pareiasaur Scutosaurus karpinskii skull by SPbU_paleontology on Sketchfab

Students and researchers can click bones of interest on a computer screen and view them at any scale and angle, or even print a 3D model for even greater clarity. At the same time, rare and complete fossils, as well as historical casts of skulls can be preserved for posterity by placing them in the museum showcases,’ added Dmitry Grigoriev.

Amphibian Dvinosaurus primus skull by SPbU_paleontology on Sketchfab

The exhibition in the Palaeontological and Stratigraphic Museum is interesting not only for the restored skulls of lizards and historical materials, but also for the diorama

‘Inostrantsevia with the Defeated Scutosaurus’ by Vitali Klatt (Paleoworldstudio, Germany). The palaeosculptor donated his work to the University’s Museum for the 160th anniversary of the birth of the outstanding palaeontologist.

Vladimir Amalitskii became the first scientist to put forward a hypothesis about the existence of a single land from the southern and northern continents in the Permian period.

His hypothesis was based on the similarity of palaeontological remains. Only a decade later, Alfred Wegener gave the single land the name ‘Pangaea’ (from Ancient Greek pan ‘all, entire, whole’ and gaea ‘Earth’). Professor Amalitskii established the similarity of fossil freshwater bivalve molluscs and terrestrial flora in the Permian deposits of Russia, Africa and India. Later, Vladimir Amalitskii, together with his wife, found bones, and then the first skeletons of lizards in Russia. It was found that they also have similarities with the dinosaurs found in the Permian deposits of Africa. Thus, the hypothesis of the unity of the continental biota of the southern and northern continents was brilliantly confirmed.