"The magnificent diversity of nature": experts from the Hermitage and St Petersburg University find secret gardens in works of art

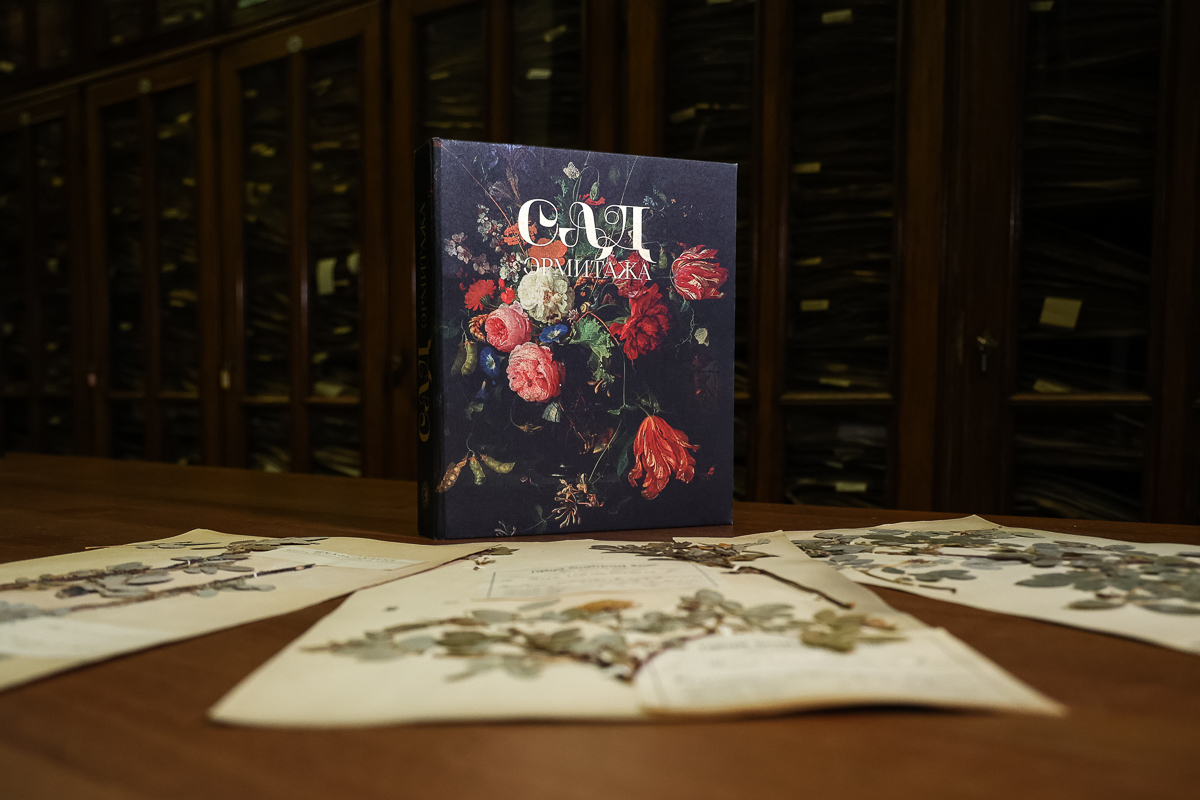

Botanists from St Petersburg University and experts from the State Hermitage Museum have analysed over 200 works of art from the Museum’s collection of Netherlandish painting and decorative and applied art of the 16th—19th centuries. The most popular among the depicted plants is the rose and species of the genus Rosa, both familiar to us today and old varieties cultivated before 1867. The findings of the interdisciplinary research are published in the Hermitage Garden Book. The publication was prepared by the State Hermitage Museum, the Hermitage Museum 21st Century Foundation, and St Petersburg University as part of the innovative international project ‘Molodost’ (‘Youth’) initiated by the State Hermitage Museum.

Scientific art

The Hermitage Garden Book is a continuation of the collaboration between art historians from the State Hermitage Museum and scientists from St Petersburg University. Last year, the Hermitage curators collaborated with entomologists from St Petersburg University in a project aimed at studying images of butterflies on the objects in the Museum’s collections. The research findings were published in the book "Butterflies of the Hermitage". The next joint initiative was to publish an illustrated album — an encyclopaedia of the images of plants found in the State Hermitage Museum’s collection of Netherlandish art. The Hermitage Garden project is a large-scale interdisciplinary study at the intersection of science and art. Members of the Youth Advisory Council of the Molodost project took an active part in the Hermitage Garden project.

This project is a new form of life for both art and science. In this publication, the 21st century scientists ‘collaborate’ with artists of the 16th-18th centuries. In this ‘collaboration’, a very subtle form of modern scientific art is born.

Anastasia Yarmosh, Vice-Rector for Strategic Development and Partnership at St Petersburg University

‘This project enabled us to bring the past and present together, actively engaging young researchers and encouraging the public to view art in a different context. We can say that we made a gift to art lovers and opened to the public an amazing world described in the words of scientists of the present and seen through the eyes of artists of the past,’ said Anastasia Yarmosh, Vice-Rector for Strategic Development and Partnership at St Petersburg University.

Zorina Myskova is Chair of the Board and Director of the Hermitage Museum 21st Century Foundation and the producer of the publication. According to her, the Hermitage Garden Book will be of interest to both art lovers and professionals, scientists and scholars in various fields of knowledge and, of course, to young people.

‘As far as we know, there is no project like this currently underway anywhere in Europe. Indeed, there are some individual studies; however, such a systematic research that aims at searching for and identifying plants featured in works of art is a unique project undertaken by the State Hermitage Museum and St Petersburg University. I hope we will continue creating unique products of the same high level of excellence together with St Petersburg University, the university that is capable of conducting such innovative, analytical, comprehensive, and profound research,’ said Zorina Myskova.

While working on the Hermitage Garden project, St Petersburg University botanists studied over 200 paintings and everyday objects from the State Hermitage Museum collections and identified at least 219 plant species belonging to 166 genera and 65 families.

As the experts from St Petersburg University explain, only thanks to the skills of the Dutch artists of the 16th—19th centuries, who paid great attention to authenticity and accuracy of detailed drawings, it was possible to identify so many plant species. It was much more difficult to recognise plants depicted on decorative items and everyday utility objects, such as plates, vases and tiles. And it is simply impossible to identify plant species in Old Dutch lace patterns. In addition, we cannot but mention the natural history diagrams from the State Hermitage Museum collection. They are exquisitely accurate, right down to the tiniest details; and some of the plant species are found only there, including: Chinese lantern (Physalis alkekengi); flowering carrots; common chicory; pheasant’s eye (Adonis aestivalis); Jacob’s ladder (Polemonium caeruleum); and others.

Interestingly, when studying works of art, St Petersburg University botanists did not come across any fantasy plants at all. This means that in a significant number of cases, artists worked either from life or from memory. Sometimes there is a share of fantasy; yet still, the images always had a real-life basis. On the other hand, the scientists noted that canvases featuring multiple plants quite often depict flowers with different blooming seasons. Spring and summer blooms — sometimes even spring, summer and autumn blooms — appear together, for instance, lilies of the valley with roses or tulips with lilies, and so on.

Floral motifs also prevailed in lace designs, which is largely due to the emergence of botanical gardens. Tatiana Kosourova is Head of the Decorative and Applied Arts Sector of the Department of Western European Applied Arts at the State Hermitage Museum. She noted that the interpretation of flowers in lace was different — compliant with the general style trends in applied arts.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the tulip became the main hero of lace ornaments, while in the Baroque era, lace-makers’ most favoured motifs were large curls of lush acanthus shoots with stylised leaves and flowers.

Tatiana Kosourova, Head of the Decorative and Applied Arts Sector of the Department of Western European Applied Arts at the State Hermitage Museum

‘Angleterre lace featured cropped flower designs, arranged in densely packed motifs, with almost no free space on the item. In Binche lace, a delicate pattern of branches with large flowers or bunches of tulips was often complemented by individual flowers. This demonstrates that in lacework, there were different approaches to depicting plants. This also testifies to the interconnection between culture, lace weaving techniques and what lacemakers would choose as the main motif of their design,’ explained Tatiana Kosourova, Head of the Decorative and Applied Arts Sector of the Department of Western European Applied Arts at the State Hermitage Museum.

"We started from a rose garden"

According to the project participants Valentina Bubyreva and Aleksandr Khalling, a significant number of the images analysed by St Petersburg University botanists are ornamental plants, mostly grasses or shrubs, arranged in bouquets and wreaths. The champion among them is the "queen of flowers" — the rose, depicted in 76 paintings.

For this particular reason, the Staraya Derevnya Restoration and Storage Centre of the State Hermitage Museum has recently laid out its own rose garden as the physical embodiment of the Hermitage Garden project. The garden will feature both heirloom roses and modern, popular varieties.

The Rosaceae family includes shrub roses that produce rose hips — they usually have five petals, as well as double-flowered varieties. These are large multi-layered flowers with extra petals of different shades that are included in the group of old garden roses. An old garden rose is a rose variety that existed before 1867. This is the year when the first hybrid tea rose named "La France" was introduced.

‘In the paintings depicting the Virgin Mary and the Holy Family, white roses often appear as a symbol of Mary’s innocence and purity. They probably belong to the Alba roses — an old hybrid between the Damascus rose and the wild rose, which was grown in the Middle Ages for medicinal purposes. In addition to white roses, Madonna lilies (Lilium candidum) can be also seen in such paintings as a flower of purity and innocence,’ explained Valentina Bubyreva, a leading specialist in the Department of Expositions and Museum Collections of St Petersburg University.

The second most popular ornamental plant was the tulip (Tulipa sp.) — it is found in 46 works of art. Almost all of the depicted plants are variegated varieties, cultivated in the 1610s—1620s. They immediately gained immense popularity that turned into a speculative frenzy over tulip bulbs — the so-called tulip mania, which ended by 1637. Interestingly, people at the time were mostly attracted by variegated red-yellow tulips. No one could have guessed then that such a colour of the petals indicates a disease — viral variegation, which is easily transmitted and leads to the death of the plant.

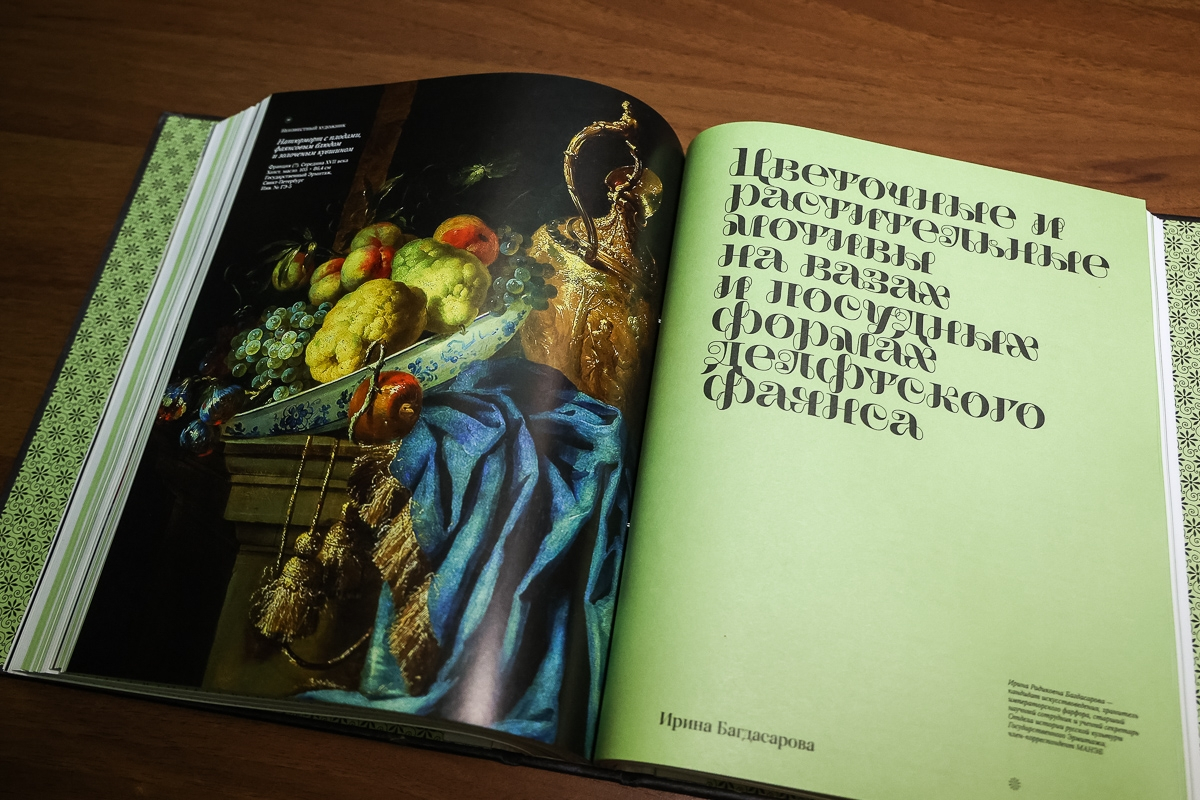

Apart from roses and tulips of various colours and shapes, the paintings and everyday objects from the State Hermitage Museum collection of Netherlandish painting and decorative and applied art of the 16th—19th centuries also feature: irises; daffodils; pink, white and red poppies; lilies and other less popular blooms. Among the fruits depicted in artwork, most often — in more than 40 cases — the botanists identified the common grape vine (Vitis vinifera), sometimes only its leaves. Other fruits that appear much less often, mainly in still lifes, include: cherries; apricots; strawberries; gooseberries; red currants; walnuts; tangerines; lemons, oranges; figs; pomegranates; pineapples; and some others.

Naturally, the botanists identified tree species as well. As a rule, they appear in landscapes or genre scenes, and sometimes as part of bouquets and wreaths. Most often artists depicted European oak (Quercus robur) — it appears on 25 works of art.

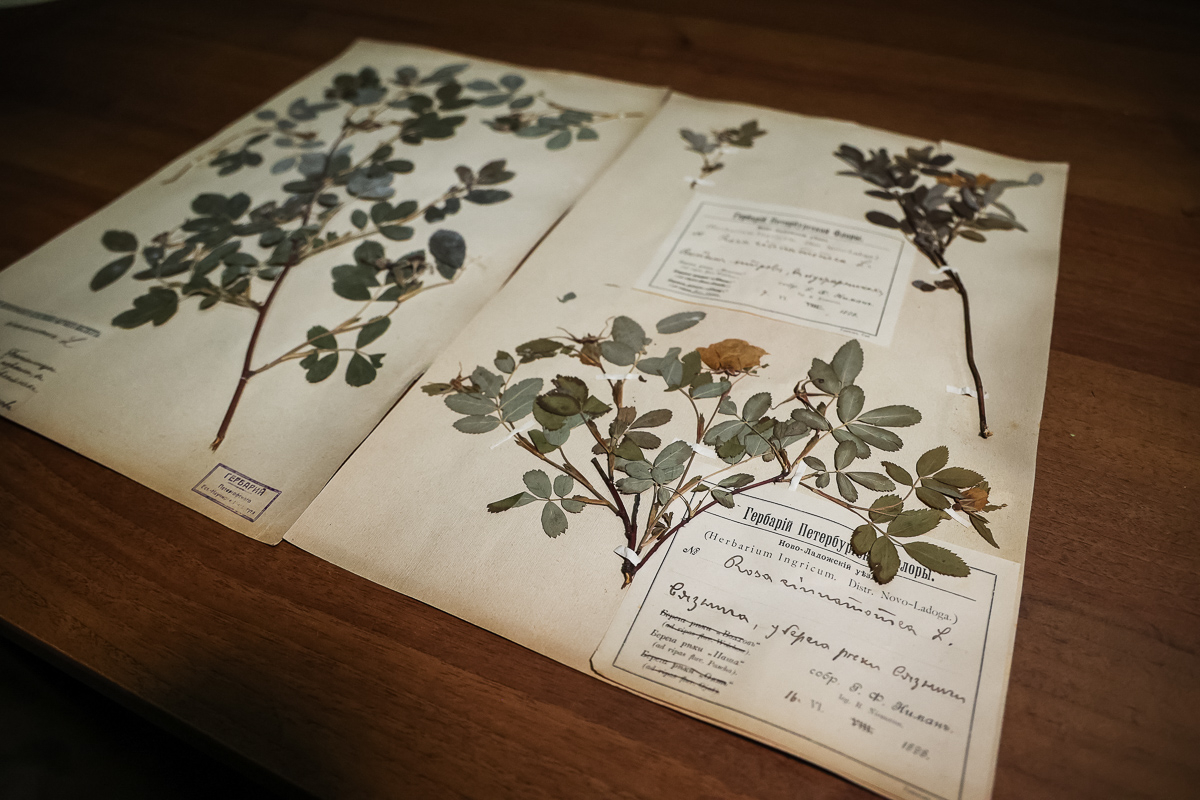

The leaves or flowers of almost all plants that appear on the pages of the illustrated edition of The Hermitage Garden Book are kept in the collection of the Herbarium of St Petersburg University. It is one of the oldest herbaria in Russia — it was founded in 1823.

Painting as a reflection of nature and emotions

Since the dawn of time, art has reflected the human experience — emotions, feelings and the everyday life of people living at the time when the artwork was created. Sometimes paintings also reveal common misconceptions. For instance, in the painting of the Dutch artist Hendrick Goltzius "Adam and Eve: The Fall of Man", created in the early 17th century, we see Adam and Eve under an apple tree. Yet, the only fruit tree that we know must have grown in the Garden of Eden is a fig tree (Ficus carica L.). Apple is just a translation error.

In their paintings, the artists depicted the knowledge available to them at the time. Not knowing for sure what the Holy Land looked like, they brought to the canvas the world as they imagined it.

In the painting "Lot and His Daughters" by Joachim Wtewael, we can also see an apple tree, although at the time of Christ there were no cultivated apple trees in Palestine.

Indeed, one of the most popular reoccurring themes in art is mythology and religion. For example, in the still life painting "Fruits and Flowers" by Leopold von Stoll, the bluecrown passionflower (Passiflora coerulea L.) is depicted in such a way that all parts of the flower are clearly visible to the viewer. The passionflower was first discovered in the New World in the 17th century and was presented to the Old World by Jesuit missionary priests. It symbolically represents the Passion of Jesus Christ.

The three stigmas represent the three nails that held Jesus to the cross. The corona filaments represent the crown of thorns that Jesus wore before his crucifixion, while the five anthers symbolise five wounds that Jesus suffered when he was crucified. The pointed tips of the spear-shaped leaves were taken to represent the Holy Lance that pierced the side of Jesus when he hung on the cross. The dark spots under the leaves are the 30 pieces of silver that tempted Judas to betray Christ. Based on its symbolism, the Jesuits named the flower Flos Passionis, from the Latin "passio" — suffering and "flos" — flower.

The participants in the joint research initiative of the State Hermitage Museum and St Petersburg University believe that a combination of art and science is becoming more and more relevant today. This is a special way to recognise the artistic value of artwork and to apply scientific knowledge, and this collaboration should continue and expand further.

The Hermitage Garden Book contains articles authored not only by the art historians from the State Hermitage Museum and St Petersburg University botanists, but also by other academics from St Petersburg University. Among them is Professor Tatiana Chernigovskaya, Director of the Institute for Cognitive Studies at St Petersburg University, who focused on the perception of paintings and their interpretation. Alongside experts and academics, students from St Petersburg University with interest in different fields of study also participated in the publication as authors. Thus, students Anastasiia Saganenko and Anna Myskova wrote about optics of a flower — its "eyes", or rather, epidermal cells with optical properties that plants have.