St Petersburg University zoologists isolate three families of tardigrades and disprove the claim about the discovery of a new genus

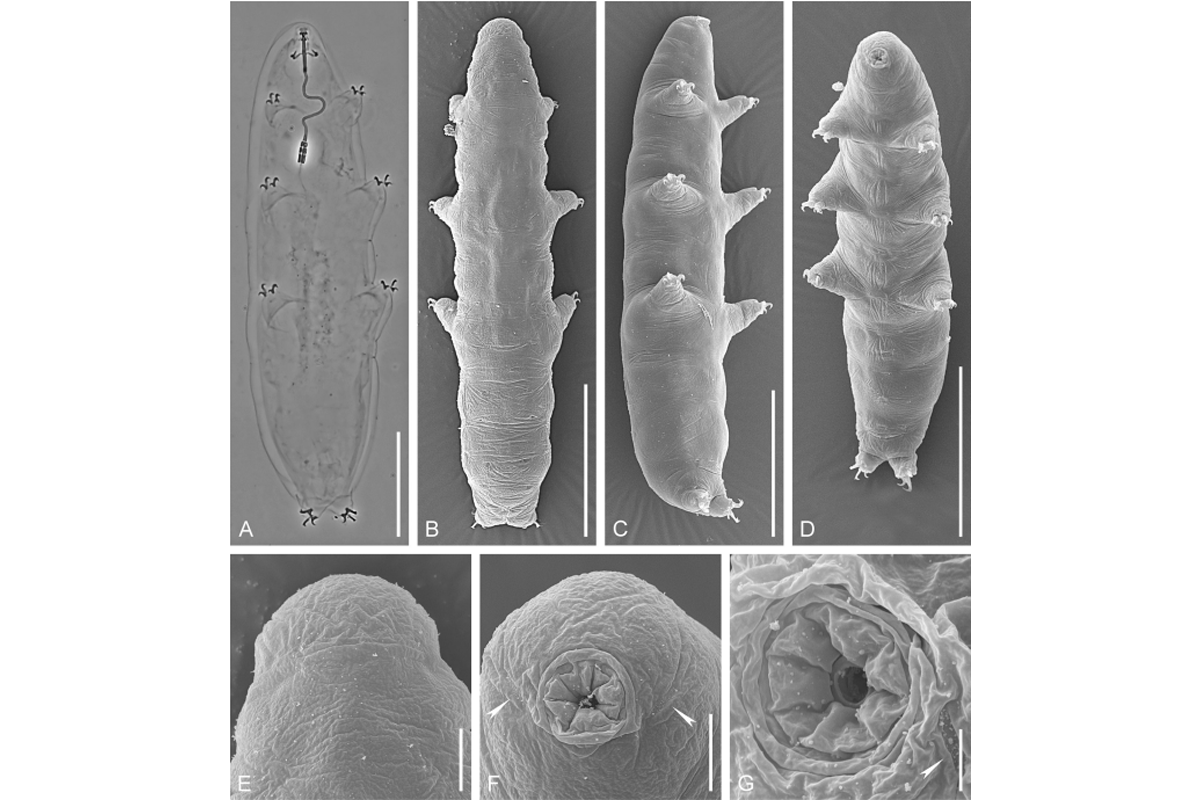

Zoologists at St Petersburg University have studied the morphological traits of four tardigrade species within the superfamily Hypsibiidae. Following the results of the phylogenetic molecular and morphological analysis, the taxonomic structure of the group has been revised, with three separate families having been isolated within the Hypsibiidae. This also enabled the scientists to disprove the claim about the discovery of a new genus within the Hypsibiidae.

First discovered in the 18th century, tardigrades are micro-invertebrates, about one millimetre in length. Tardigrades are renowned for their extreme stress tolerance and adaptability. They can hibernate for as long as necessary in order to be able to survive in the harshest conditions, even in outer space. As a rule, tardigrades inhabit moss and lichen cushions, where they reproduce and feed on the fluids rich with micro-algae and other plants, as well as on microscopic animals sharing the same habitat.

The research findings are published in the journal Zoosystematica Rossica

For a long time, the taxonomy of tardigrades was based solely on their morphology. With the introduction of molecular taxonomy methods, however, scientists have discovered significant discrepancies between the results of molecular reconstructions and traditional morphological methods in the analysis of the animal phylogeny, determining the relationship within a group. As the researchers explain, the conventional understanding of tardigrade evolutionary history is not always correct, and detailed analysis of the morphological structure often confirms hypotheses based on phylogenetic molecular data.

In particular, tardigrades are distinguished by a limited set of morphological characters available for the phylogenetic analysis and identification, which is associated with the small size of these invertebrates. When analysing the morphology and functional anatomy of tardigrades, it is extremely difficult to identify and distinguish unique morphological traits, characterising related groups of tardigrades, from the traits inherited from a common ancestor that cannot serve as evidence of group kinship.

Our research prompted us to re-evaluate the structure of the superfamily Hypsibioidea. Our recent findings, including the results of the phylogenetic molecular and morphological analyses, made us realise that there are practically no common traits (neither morphological, nor molecular) that unite separate groups within the largest family of this clade — Hypsibiidae.

Denis Tumanov, Assistant Professor in the Department of Invertebrate Zoology at St Petersburg University

‘We therefore proposed to isolate within the Hypsibiidae three full-fledged families, differentiated by these traits,’ explained Denis Tumanov, Assistant Professor in the Department of Invertebrate Zoology at St Petersburg University.

The zoologists at St Petersburg University made a new integrative description of an Arctic species of Diphascon tenue, which was first described and established back in the early 20th century based on its morphological characters. The results of molecular analysis enabled the University zoologists to conclude that this species does not belong to the genus Diphascon. Yet, its morphological characters appeared to confirm its inclusion within the genus Diphascon. Another Antarctic tardigrade species investigated in the same study had the reverse situation. The molecular data allowed for its attribution to the genus Diphascon, while the morphological data did not support that. Hence, the conclusion was drawn that this tardigrade family structure needs re-evaluation.

More specifically, such a conclusion was made based on the detailed analysis of the bucco-pharyngeal tube structure; in particular, the presence or absence of a drop-like thickening between the buccal and pharyngeal tubes, where the pharyngeal muscles are attached. Previously, this morphological trait was considered a key determinant in dividing the species groups within the family Hypsibiidae. The study of the University zoologists showed that, along with other morphological characters, this trait is distributed within the Hypsibiidae without reference to any specific taxa. In other words, this might be an ancient trait lost in some groups.

Having analysed several other members of the family Hypsibiidae, the scientists concluded that this family should be divided into three separate groups, which had been previously considered subfamilies. In fact, two of them were regarded as two separate families, but were later merged into one, whereas the third subfamily has been recognised relatively recently.

St Petersburg University, the oldest university in Russia, was founded on 28 January (8 February) 1724. This is the day when Peter the Great issued a decree establishing the University and the Russian Academy of Sciences. Today, St Petersburg University is an internationally recognised centre for education, research and culture. In 2024, St Petersburg University will celebrate its 300th anniversary.

The plan of events during the celebration of the anniversary of the University was approved at the meeting of the Organising Committee for the celebration of St Petersburg University’s 300th anniversary. The meeting was chaired by Dmitry Chernyshenko, Deputy Prime Minister of the Russian Federation. Among the events are: the naming of a minor planet in honour of St Petersburg University; the issuance of bank cards with a special design; the creation of postage stamps dedicated to the history of the oldest university in Russia; and the branding of the aircraft of the Rossiya Airlines to name just a few. The University has launched a website dedicated to the upcoming holiday. The website contains information about outstanding University staff, students, and alumni; scientific achievements; and details of preparations for the anniversary.

Additionally, the researchers from St Petersburg University have clarified the phylogenetic position of a recently described genus Meplitumen within the Hypsibiidae.

‘This genus was described using morphological data from South America. In most of its morphological traits, this genus is similar to another genus within the superfamily Hypsibiidae. The key morphological character was some details of its flexible pharyngeal tube structure. Based on this particular morphological character, another species — found in Europe long ago — was later attributed to this genus. We found that the trait, initially regarded as unique to this genus, was in fact present in another long-known genus. Then, we carried out phylogenetic molecular analysis. It turned out that the representative of the genus — initially found and described in South America a few years ago — that we have recently found in Russia fits within the long-established genus. Hence, the Meplitumen cannot be considered a separate genus,’ Denis Tumanov explained.

Thus, in addition to discovering a new genus of tardigrades, the zoologists from St Petersburg University also managed to ‘close’ the genus Meplitumen.

Earlier, the scientists from St Petersburg University discovered four new species of tardigrades and found three other tardigrade species new to Russia, previously only found in other countries. Also, the scientists from St Petersburg University, as part of an international team of researchers, have re-evaluated the morphological diagnoses of tardigrade species found in Antarctica, Great Britain and Italy and proposed a new family of these microscopic invertebrates — Acutuncidae.